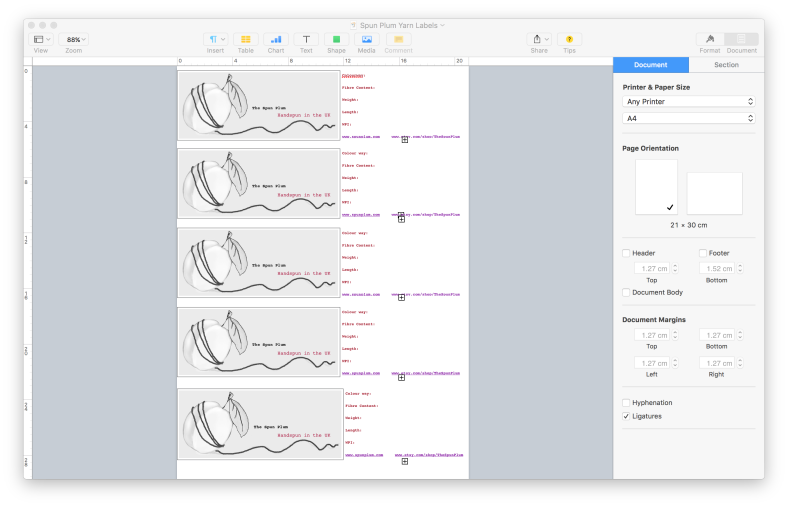

It’s about time I continued my posts about knitting with handspun yarn, especially now that my lovely Etsy shop (check it out here) is up and running and people are actually buying my yarn to knit with. In my first post about knitting with handspun (Knitting with Handspun Part 1: Beginnings and Pullovers) I covered some of my earlier handspun knitting adventures. This time I’m going to focus specifically on some shawls that I’ve made with my yarn and what I’ve learned along the way.

First of all, I have to confess that I am predominantly a sweater knitter. It would seem that knitters fall into categories of what they like to knit the best: sock knitter, mitten knitter, shawl knitter, sweater knitter. I’m definitely the latter. I love knitting sweaters and do that the most. Accessories are usually in-between projects to me, to break up the time that goes into knitting a complete sweater.

Having said that, I have loved pretty much every sock, mitten, slipper, hat and shawl project that I’ve done. Also, shawls are a lovely way to show off beautiful yarns without using large quantities. A lovely handspun skein combined with other nice yarns makes a beautiful shawl. You don’t need to worry about fit, and there are so many patterns out there for lovely striped and geometric patterns that highlight a beautiful yarn and great colour combinations.

Above is the beginning shot of my most recently completed shawl; a cozy beast that I wear on almost a daily basis. I knit it using some lovely handdyed yarn that I purchased as a treat from my friend’s shop Phileas Yarns. The grey yarn is handspun that I made specifically for this project. It’s un-dyed grey Massam, spun as a single to match the gauge of the green yarn. Here it is below in its in-progress state, showing off its lovely halo and long-wool texture.

This project was great because the exact gauge of the handspun sections didn’t really matter. They were worked as short row ‘clouds’ and so the slight variation in handspun texture didn’t affect the shape of the shawl.

The finished result:

This felt like a real success, particularly in comparison with my first handspun shawl:

Behold the Transcontinental Alpaca and Three Sheep Shawl: A product of wool geekery, in which I got a thrill out of knitting with three breeds of sheep and alpaca from two continents. This was a completely handspun project and I was very excited about it. The end result was a bit crazy looking, but I was totally in love with it. I knit it from the following yarns:

Clockwise from top left: Australian alpaca blended with Canadian alpaca, dyed and undyed; thread plied, undyed merino cross; handpainted ryeland; handpainted BFL

I’ve mentioned this shawl before in a very early post about ryeland fleece ( A Weekend With The Oldest Sheep in England) Basically, the ryeland has a springy cobwebby texture, which evidently stretched during knitting and gradually retracted over the course of a few weeks, meaning that the shawl started to shrink and warp. I eventually pulled it out and learned this very important lesson, which is now my second knitting with handspun tip:

You can’t always mix fibres and yarns as if they are identical

Different yarns behave differently. Different fibres certainly behave differently. And there are a lot of different factors involved in why. In this case I took a super squishy alpaca, combined it with the springy retractable ryeland, and then added in a soft, but hardwearing BFL which had been tightly plied. The result was that while the alpaca bloomed and fluffed during blocking, the ryeland shrank, and the BFL just hung there draping beautifully, but not moving at all. The result: a warped shawl.

The solution is to gauge swatch, take little samples and block them, and be careful with how you combine very different handspun yarns in a project. The green shawl above was successful because the handspun sections could behave however they liked and it didn’t throw off the rest of the shawl. My multi-fibre handspun shawl was a triangle shawl with centre increases so that every row depended on each other and each half of the shawl was integral to the other.

I had to think about this just yesterday when I finished up with the above skein of yarn and listed it in my shop. This is a self-striping yarn that changes back and forth between hand-dyed merino and undyed, natural cream Massam. It has a lovely combination of textures. However, knitting with it will require a good gauge swatch because of the striping between the two fibres. The merino is soft and squishy and is far more compact-able than the massam. This means that the gauge that it’s knit in will have to work for both fibres and both of them need to be swatched for. While the merino can squash down to a fluffy and tight gauge, the same tight gauge on the Massam will not drape as nicely because it won’t squish down the same way. A looser gauge that works for both and allows them to both move and drape nicely will be required.

Now on to my last handspun knitting tip:

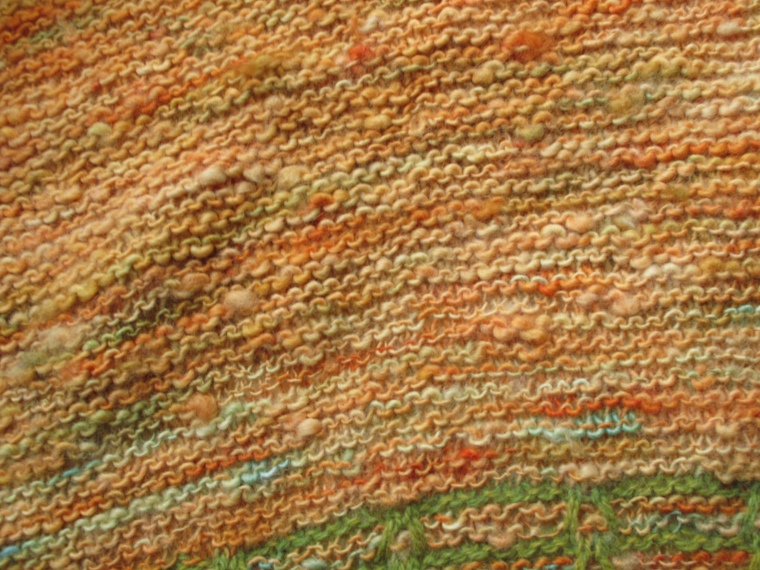

Above is an almost-complete shawl, which I’ve since decided to modify and have pulled back. I knit it from an all-time favourite handspun single which I spun from the fold with the fleece from Clive the pet sheep. This yarn was one of my first times hand-painting. I loved it so much and purchased as special skein of naturally hand-dyed camel/alpaca/merino blend to combine with it.

I used the pattern Byatt by Karie Westermann which calls for a specific brand of yarn, 100g of each colour. I had 100g of the handspun skein and 50 g of the other one, so I thought at some point I’d spin or dye up another 50 g of contrast colour and finish it off that way. However, what I didn’t take in to account is that, unlike with most commercial yarns, you can’t really estimate how much you have by weight. I usually think to myself that 100g of fingering weight is enough for a pair of socks, 450-550g for an aran weight sweater, 300-400g for a fingering weight sweater, 200 g of anything for a shawl, etc. However with this shawl, I ran out of the handspun really really quickly, which is too bad, because it knit up really nicely.

Lovely “from the fold” texture, great colour variegation, and all in all a nice way of showcasing a raw fleece yarn. However, because I ran out so quickly, I had to completely readjust the pattern and then ended up running out of my contract colour too quickly as well, which threw everything off. My solution was to dye up another contract colour and swap it in to the pattern with my other contrast colour as soon as I ran out of handspun. The result is nice, but it’s pretty disheartening to pull back so much work. I could have avoided this if I’d actually paid attention to the yardages I had and the yardages that I needed, and had planned from the beginning.

So the last tip is:

Judge the amount you need by yardage and not by weight

This especially applies to yarn that’s been spun from the fold from raw fleece. The natural kinks and slubs that make yarn handspun from fleece so lovely can also make it heavier, meaning that you have less yardage for every 100 grams. Yarn like this has little pops of felt that give a beautiful organic texture and speak to the origin of the yarn. Fleece felts on the sheep as it rubs against things, stands in the rain, sleeps in the field, and basically lives its life outdoors. Including these felted fleece bits in the yarn feel, to me, like including a bit of the sheep’s story into the work. But you can’t underestimate how dense and heavy they can be. Commerically combed and spun yarns and some hand-carded handspun yarns can have a lot of yardage for less weight because they have a lot more air in them. Spun-from the fold yarns may have a lot more story in them, but they are much denser.

I will continue to knit with my own handspun, so more handspun knitting posts will follow in the future!